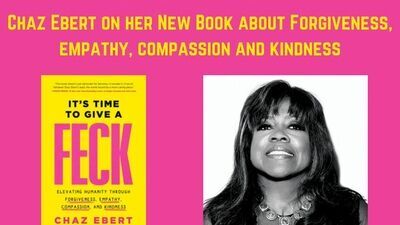

You make an important point in your discussion of Archbishop Desmond Tutu that forgiveness is not only a spiritual obligation but in the most practical sense “political expediency.” Many people might think that because an act helps to achieve a political goal it is somehow less “pure.” What do you think?

Yes, that’s a good observation. Because Archbishop Tutu was a man of the cloth you would think that his basis for forgiveness would be only the bible. And yes, he does talk about the biblical basis, but he also expounds on the political expediency. He and President Nelson Mandela led the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to unify South Africa after the abolishment of apartheid. He said he lost many friends over it because some people wanted revenge more than reconciliation. However, they knew that after a publicly remorseful confession of wrongs by the offenders under the old apartheid system, there had to be a road to redemption in order to avoid bloodshed. That is no less pure than any other type of forgiveness.

Roger famously called movies “empathy machines.” Do you have three or four favorites you found especially powerful?

I loved Roger’s emphasis on empathy. One of my favorite movies when I need a good cry is “Terms of Endearment.” Shirley MacLaine’s character is tough and not very warm, so at first you shy away from her. But you empathize with her pain when she is at the hospital bed of her daughter played by Debra Winger. One of the movies that I mention in the book is Ava DuVernay’s “Selma.” She found different ways to help us empathize with characters, even those like Dr Martin Luther King,Jr, (who was portrayed by David Oyelowo) who is usually presented as more of an icon than a real-life man. She humanized him. But you don’t have to have a serious movie to exhibit empathy. One of the best empathetic movies is the animated feature “Inside Out.” There, they literally label each emotion of the little girl Riley, and let you experience those emotions along with her.

Your book has many wonderful examples of acts of forgiveness, empathy, compassion and kindness, and often the smallest gestures are the most meaningful. My favorite is the one about the health care professionals putting photos of their faces on their PPE garb. Another was just about saying, “Hello.” Why do those actions make a difference?

We think that unless we have the majesty of a Nelson Mandela or an Archbishop Desmond Tutu, our actions don’t count, but they do. Even the smallest gesture of compassion or kindness can change someone’s life for the better. I spoke with neuroscientists while researching this book who told me that more and more research is proving that acts as simple as saying hello to our neighbors have an affect on our state of well-being. And there is no doubt that the healthcare workers who cared enough to tape photos of themselves on their PPE gear so that their little patients felt a connection to a real human being provided a measurable uplift. It made those patients feel less isolated and afraid. And that is what is the most exciting about the stories in the book. You will find that you don’t have to be “born” with it, you can develop the muscles of empathy, and compassion and kindness and even forgiveness by practicing them in ways big or small on a consistent basis.

Leave feedback about this