“Mami Wata” is populated by men and women who dress and act as if they’re still in a previous century, resisting modernity. The title refers to the Nigerian goddess of water, wealth, and health, who watches over individual lives. This is a matriarchal society. The anointed priestess and interpreter of Mami Wata, as well as the arbiter and problem-solver for everyone in the village, is Mama Efe (Rita Edochie).

Mama Efe is powerful and respected, but some of her people are starting to feel that she’s losing her connection to the goddess or that she is too set in her ways to understand that the village can only survive if it adapts to modern life. Mama Efe has two children: her biological daughter Zinwe (Uzoamaka Aniunoh) and her adoptive daughter Prisca (Evelyne Ily Juhen). Prisca is almost completely estranged from Mama Efe partly because she shares the feelings of dissatisfied fellow villagers, but there’s a personal component as well, one that transcends culture and will be understandable to anyone who fears that blood trumps every other bond. Zinwe is more loyal, but she’s got her own doubts. She wants to be reassured that the old ways are right, that the magic is strong, and that she will inherit all.

But her mother is not the force she used to be. The decisive event in the early part of the story is the death of a sick young boy. Mama Efe treats his illness the old way, with incantations and a potion. The ritual fails. The citizens confront her, demanding answers to questions they once discussed only in private. Why doesn’t the village have a doctor? Or other hallmarks of modern life—a police force, a fire station, electricity? There could be a rebellion here under the right circumstances.

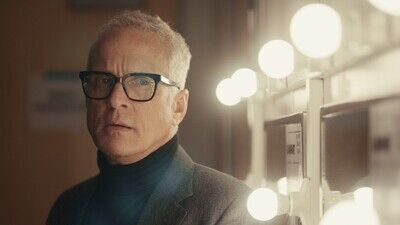

Then, a man washes up on the beach as if fulfilling a prophecy or curse. His name is Jasper (Emeka Amakeze). He exudes confidence, power, and the insinuating, dangerous magnetism that made old-school Hollywood “rebel” actors like Marlon Brando and Paul Newman so popular. Once Jasper enters the picture, the movie becomes more of a political fable, with elements of art-house film noir and crime thrillers that didn’t have much of a budget but made up for it with swaggering minimalism. The framing, blocking, and lighting of the shots (by cinematographer Lílis Soares, who won a prize for her work on this film at this year’s Sundance Film Festival) amounts to a bridge between the past and the present, which is what the characters yearn for but cannot manifest.

This is not a movie you can pick apart in terms of plausibility or real-world details. It’s a dream with its own internal logic and consistency. A person, location, or object always has a specific plot function but is imbued with other possible meanings and inspires varied interpretations.

It doesn’t explain itself. It doesn’t need to. It’s all there, in the images and performances and sounds. The dialogue is in pidgin English, with subtitles, but the acting, writing, and filmmaking are so precise that there may be times when you forget to read the subtitles. You know what these characters want. You feel what they feel. You see through their eyes.

Leave feedback about this